Explainer - Councils and the government seem at odds over massive water infrastructure reforms, so how does it affect ratepayers, and what does it mean for their water systems? Can the minister wade in and simply force the councils into the deep end?

RNZ is here to clear it all up.

Photo: RNZ / Vinay Ranchhod

What are the three waters?

Simply put, it's called three waters because it's about the three main types of water infrastructure: storm water, drinking water and wastewater.

At the moment, about 85 percent of this is managed by councils - and some do it better than others. Some smaller and rural populations, including marae, also get their water through private or community-based providers.

About 8000 people were infected by campylobacter contamination centred in Havelock North in 2016, leaving at least four dead and others permanently disabled, leaving thousands sick and costing the local health board more than $760,000.

This prompted the government to take a long, hard look at water services and how they were being delivered across New Zealand, the result being a proposed programme of reform which would see water management taken from New Zealand's 67 councils, and handed to four big regional entities.

In recent years too, Wellington has seen sewage bubbling up in the streets, and in Auckland storms have regularly led to beach closures due to sewage overflows. Drinking water supplies across New Zealand are inconsistently managed and often needs boiling.

Local Government Minister Nanaia Mahuta said it was unacceptable that every year about 34,000 people in New Zealand fell ill from drinking water, and thousands of households were required to boil their water to drink it safely.

Reports from the Water Industry Commission for Scotland, reviewed by engineering firm Beca, suggest between $120 billion and $185 billion is needed over the next 30-40 years to get water systems across the country up to standard.

How did we get here? (water flowing underground)

A timeline:

- August 2016: Havelock North water contamination crisis (see above)

- May 2017: Official inquiry into crisis criticises councils for failing to safeguard town water supplies.

- June 2017: Local Government Minister Anne Tolley (National) proposes a cross-agency review of the three waters to Cabinet.

- July 2019: Government inquiry into contamination recommends a dedicated regulator, stronger government stewardship of wastewater and stormwater, with regional councils regulating the environment.

- July 2020: Labour government launches Three Waters Reform Programme, costing an estimated $761m, which mayors expect will be the biggest shake-up to water since 1989. It also passes the Taumata Arowai Water Services Regulator Bill.

- September 2020: Hawke's Bay councils' report warns of overwhelming rates bills and crippling debt if water problems not fixed.

- March 2021: New independent water regulator, Taumata Arowai, established.

- April 2021: Local Government Minister Nanaia Mahuta announces an independent review of local government.

- June 2021: A day before the full plan is announced, Whangārei council is the first to opt out of the reforms. Mahuta makes further detail on the plans public, announcing the four-entity model. Other councils begin to express unease over the plans.

- July 2021: National and the Greens raise concerns that a lack of council buy-in could mean the government is forced to make the reforms mandatory. The government offers councils $2.5bn to opt into the reforms, aiming to leave no council worse off from the reforms and ensure consensus.

- September 2021: The Water Services Bill passes, handing drinking water regulation from Ministry of Health to Taumata Arowai and strengthening drinking water regulations, including with increased penalties. Most councils appear to be against the reforms going ahead.

- October 2021: Two-month consultation period for councils to respond to the reform proposals ends.

Regulation - Taumata Arowai

One of the changes proposed, fairly uncontentious, is the establishment of a new drinking water regulation body called Taumata Arowai.

Drinking water regulations had been managed by the Ministry of Health, but with the passing of the Water Services Bill into law, Taumata Arowai will oversee, administer and enforce all of New Zealand's drinking water regulations.

It will also provide oversight of environmental performance of wastewater and stormwater networks.

It is an independent Crown agency with a minister-appointed board and minister-appointed Māori advisory group. Mahuta in February announced former Director-General of Health Dame Karen Poutasi would chair the inaugural board, with other appointments including Troy Brockbank, Riki Ellison, Brian Hanna, Dr Virginia Hope, Loretta Lovell, and Anthony Wilson.

The regulations will be backed up by significant penalties, including fines and criminal proceedings.

Drinking water suppliers have a year from when the Water Services Bill passed to register with Taumata Arowai.

Suppliers already registered with the Ministry of Health - mostly councils - have a year to comply with the new requirements. Those who are not have four years register with Taumata Arowai, and seven years to get up to snuff.

Local Government New Zealand - the councils association - supports the idea.

There are also plans for a second regulator, which would be a financial watchdog for the water management entities, reducing the risk of underspending on water while still aiming to keep costs to ratepayers down.

Running water: Governance, ownership concerns bubble to surface

While councils largely agree investment is needed across much of the country, most still oppose the government's reforms, largely over ownership and governance.

Councils have spent years, and huge sums in ratepayer funding, building and maintaining their water infrastructure assets.

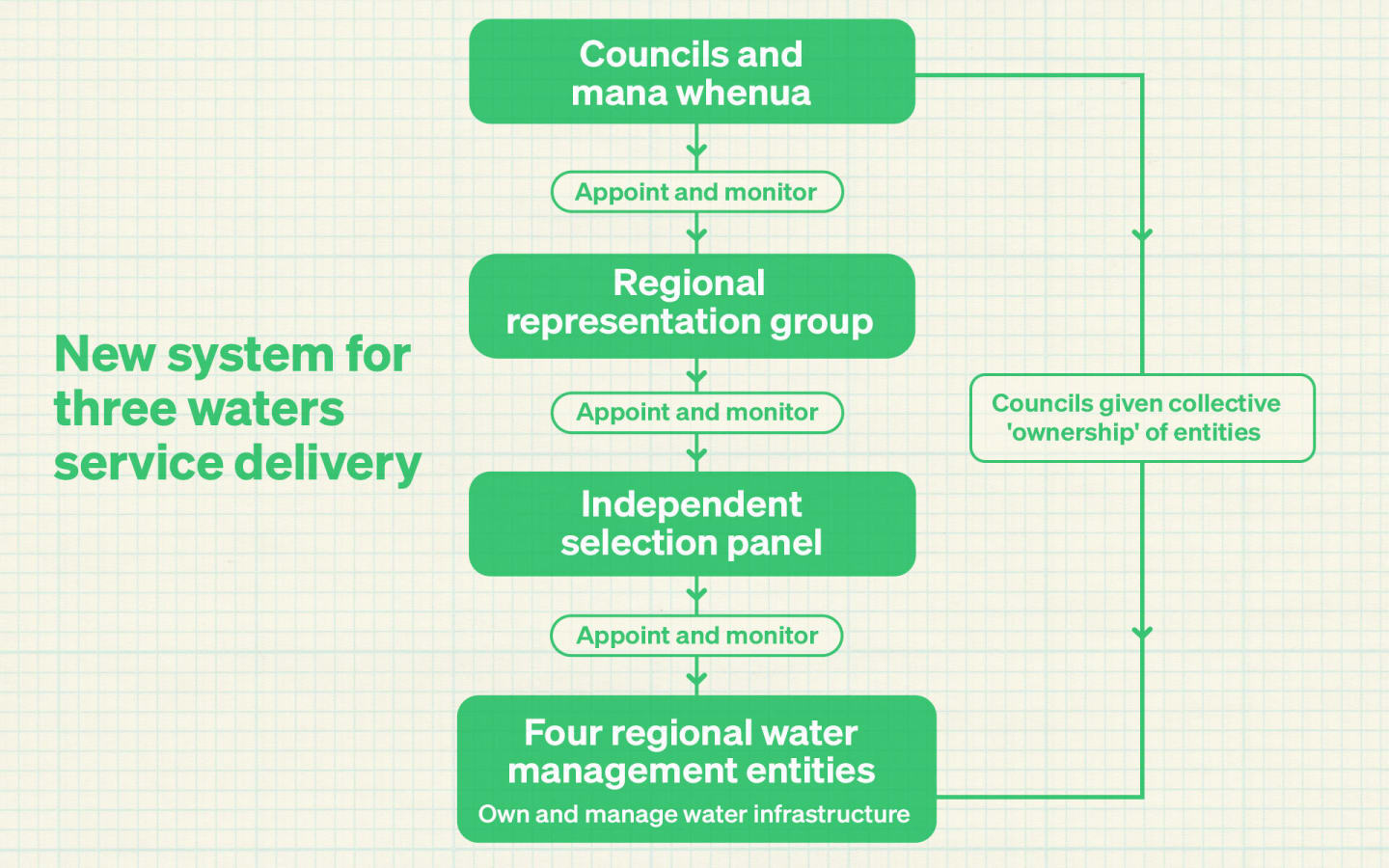

While Mahuta has repeatedly said there would be public ownership of these systems, the documentation shows the four new entities would "own and operate three waters infrastructure on behalf of local authorities, including transferring ownership of three waters assets and access to cost-effective borrowing from capital markets to make the required investments".

It says ownership would be transferred to four entities, which themselves would be collectively owned by the councils they service.

Many councils argue they have done a good job with their water infrastructure, or have plans in place - with money already set aside - to manage the shortfall.

They worry combining their assets with others that require much more investment would mean their ratepayers, who have already paid the price for good water services, paying again for those who have not.

Some $2.5 billion has been set aside by central government to even out this playing field, aiming to take the sting out of these concerns. Of that, $2bn would be apportioned out to smooth the differences, and $500m would go to supporting councils in transitioning to the new arrangement.

Some fear it would not be enough however, with Whangārei mayor Sheryl Mai saying it fell far short of the value of assets the council would be losing control of.

"We have no debt against this asset class ... the total package I think came to around $133 million, which sounds like a lot of money, however the assets have a value of between $600m and $1.2bn depending on whether you're doing replacement value so, frankly ... that's not sufficient for us to say that's a good deal when we're losing the control."

Councils are also concerned about how the entities would be managed.

Documents show they and mana whenua representatives would jointly appoint a regional representative group, who would manage concerns, strategy and expectations of the entities.

This group would appoint an independent selection panel, which would in turn appoint the board which manages and runs the entity. It's not hard to see why some councils fear their control and authority over their water services would be, at the very least, watered down.

With health reforms set to also take power away from elected representatives, they may well fear the effect of losing input on some of the services that have been central to local government in New Zealand for many years.

Photo: RNZ / Vinay Ranchhod

National's Local Government spokesperson Chris Luxon likens it to a "bewildering series of Russian dolls".

Māori have similar fears. With many hapū and iwi Māori communities not connected to the regional drinking water supply or the wastewater system, they worry about losing control of the water systems they do have and being forced into new arrangement, with associated costs.

The case for change - is misinformation poisoning the wells?

Although most mayors and councils are not convinced by the government's solution, many agree the case for change is compelling.

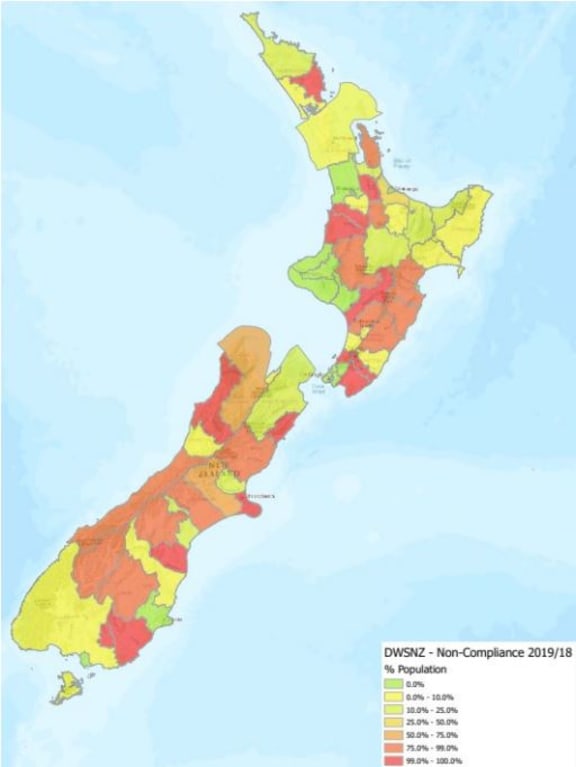

Photo: Beca, using data from the Ministry of Health Annual Report on Drinking Water Quality 2018-2019

The government's figures suggest there would be major benefits to moving to just a few, much larger, organisations which would have greater bargaining and contracting power.

They could also borrow large sums to achieve large-scale projects to deliver bigger benefits at lower cost to more people.

As it stands, Ministry of Health data shows drinking water supplies across New Zealand are often not good enough.

With harsher regulation on the horizon, Nelson's Rachel Reese says maintenance and upgrade costs will also continue to increase, exacerbated by climate change.

She says the topic has become politicised and some - including council members - are wilfully spreading misinformation.

"I can think of rhetoric that I've heard from members of my own council that doesn't reflect the facts of the proposal, and that causes the community to get anxious unnecessarily."

Some more recent independent analysis however brings some of the government's conclusions into question.

In the pipeline

With councils having provided their feedback to the minister, it's now up to the government to decide how it will proceed.

Mahuta, in a statement on Friday, said they would "consider refinements to the proposals within the government's bottom lines of good governance, partnership with mana whenua, public ownership and operational and financial autonomy".

She said she expected a final report from officials in the coming weeks, including advice on changing aspects of the proposals, after which Cabinet would consider the next steps including a public consultation process.

What this means is the three waters is far from complete, nor is it set in stone.

However, she has repeatedly refused to rule out using legislation to force the councils to toe the line, lending credence to National and Green party concerns.

"I suspect what she'll do is end up saying 'okay, there's 22 district councils in this entity all 22 can sit on a representative committee; sole responsibility of that representative committee is to appoint an independent panel, who then select a board … I suspect she'll do a tweak to that sort of arrangement and something along more participation in the representative committee.

"Then she'll look to jam it through, and make it compulsory and mandated across all councils."

The proposals also set a timeframe, calling for the new entities to be up and running by 1 July 2024, so the water clock is ticking.